The Fall of Constantinople: A Turning Point in History

The fall of Constantinople in 1453 stands as a pivotal event in world history, marking the end of the Byzantine Empire and heralding a new era of Ottoman dominance.

The Background

Constantinople, founded by Emperor Constantine the Great in 330 AD, was the capital of the Byzantine Empire and a bastion of Christian civilization for over a millennium. Its strategic location on the Bosporus Strait made it a vital hub for trade and a coveted prize for many invaders. By the mid-15th century, the Byzantine Empire had dwindled significantly, with Constantinople as its last significant stronghold, surrounded by the rapidly expanding Ottoman Empire.

The Siege

The siege of Constantinople began on April 6, 1453, led by Sultan Mehmed II, also known as Mehmed the Conqueror. The Ottomans, numbering around 80,000 to 100,000 soldiers, faced a defending force of about 7,000 to 10,000 Byzantines and their allies. Despite the defenders' valiant efforts, they were vastly outnumbered and outgunned.

Mehmed II employed advanced military technology for the time, including massive cannons capable of breaching the city's formidable walls. The most famous of these was the Basilica, a giant cannon designed by the Hungarian engineer Urban. This artillery bombardment, combined with a relentless assault on both land and sea, gradually weakened the city's defenses.

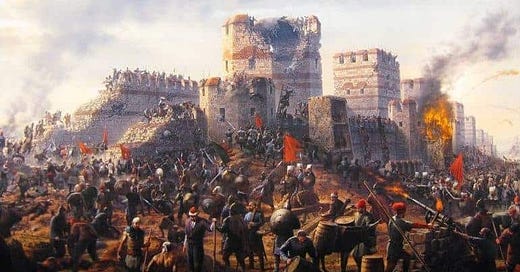

The Final Assault

After 53 days of siege, on May 29, 1453, Mehmed II launched a final, all-out assault. The defenders, exhausted and demoralized, were unable to repel the overwhelming Ottoman forces. The breach in the walls at the Gate of St. Romanus proved decisive. The Ottomans poured into the city, leading to intense street fighting and widespread looting.

The last Byzantine emperor, Constantine XI Palaiologos, reportedly died fighting alongside his soldiers, a symbol of the empire's tragic end. By mid-morning, the Ottomans had complete control of the city.

Aftermath and Impact

The fall of Constantinople had far-reaching consequences. For the Ottomans, it marked the beginning of a new era. Constantinople was renamed Istanbul and became the capital of the Ottoman Empire, symbolizing its ascendancy as a major power. Mehmed II encouraged the repopulation of the city, welcoming people of various backgrounds and religions, which helped restore its status as a bustling, cosmopolitan center.

For Europe, the fall of Constantinople was a profound shock. It signaled the end of the Byzantine Empire, a continuation of the Roman legacy, and a significant Christian stronghold. The event also prompted European nations to explore new trade routes, ultimately leading to the Age of Exploration. The loss of Constantinople as a trade hub pushed explorers like Christopher Columbus to seek alternative passages to Asia, inadvertently leading to the discovery of the Americas.

Culturally, the exodus of Greek scholars from Constantinople to the West played a crucial role in the Renaissance. These scholars brought with them classical texts and knowledge, fueling a revival of learning and arts in Europe.

Conclusion

The fall of Constantinople in 1453 was more than just the end of a city; it was the end of an era and the beginning of another. It reshaped the geopolitical, cultural, and economic landscape of the time, leaving an indelible mark on history. This monumental event remains a poignant reminder of the transient nature of empires and the enduring impact of historical transformations.